Basic examples:

doubleMe x = x + x

doubleUs x y = doubleMe x + doubleMe y

doubleSmallNumber x = if x > 100

then x

else x*2Definition

Rules

- Functions can be defined in any order.

- Functions cannot begin with a capital letter.

- All functions are non-destructive, since all data is immutable.

- A prefix function can be called as an infix function if it is enclosed in backticks.

div 12 5is the same as12 'div' 3(replace the quotes with backticks) - Function definitions are invoked in the oder in which they are defined.

When does a function call match a definition?

if the arguments in the definition are constant, the value supplied in the function call must exactly match those in the definition. For variable arguments, any parameter with matching type will work.

- Constants and variables can be mixed in a function definition

Conventions

- The ’ character does not have a special meaning in Haskell’s syntax. It usually denotes a slightly modified or strict (not lazy) version of a function.

xsseems to be a common placeholder function name.

Functions which do not take any arguments are guaranteed to always return the same value, since once defined they cannot be changed and arguments are the only way to influence a functions’s return value. Such functions are analogous to const variables in imperative languages, and are called definitions.

Type declaration

Functions are treated as expressions in Haskell, and as all expressions, have Types. We chan choose to give functions explicit type declarations. This is generally considered to be good practice except when writing very short functions.

removeNonUppercase :: [Char] -> [Char]

removeNonUppercase st = [ c | c <- st, c `elem` ['A'..'Z']]The is no no special delimiter between the parameters and the return type.

addThree :: Int -> Int -> Int -> Int

addThree x y z = x + y + zThe type of functions can be checked with :t.

Example: Multiple ways to define XOR function

xor1, xor2, xor3, xor4, xor5, xor6, xor7, xor8, xor9,

xor10, xor11, xor12, xor13, xor14, xor15, xor16, xor17 :: Bool -> Bool -> Bool

xor1 b1 b2 = b1 && not b2 || not b1 && b2

xor2 b1 b2 = if b1 == b2 then False else True

xor3 b1 b2 = if b1 /= b2 then True else False

xor4 b1 b2 = b1 /= b2

xor5 b1 b2 = (/=) b1 b2

xor6 = (/=)

-- pattern matching

xor7 False False = False

xor7 False True = True

xor7 True False = True

xor7 True True = False

xor8 False True = True

xor8 True False = True

xor8 b1 b2 = False

xor9 False b = b

xor9 b False = b

xor9 b1 b2 = False

xor10 False b = b

xor10 True b = not b

xor11 False True = True

xor11 True False = True

xor11 _ _ = False

-- guarded definitions

xor12 b1 b2

| b1 == b2 = False

| b1 /= b2 = True

xor13 False b2 = True

xor13 True b2

| b2 == False = True

| b2 == True = False

xor14 b1 b2

| b1 == True = not b2

| b2 == False = b1

xor15 b1 b2

| b1 == True = not b2

| otherwise = b2

xor16 b1 b2 = case b1 of

False -> b2

True -> not b2

xor17 b1 b2 = case b1 of

False -> case b2 of

False -> False

True -> True

True -> not b2Currying

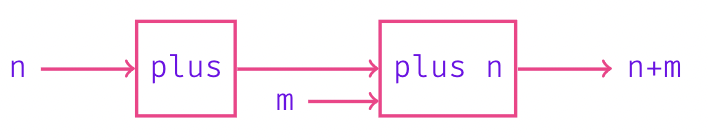

In Haskell, functions are fundamentally capable of taking only one argument. Multi-parameter are implemented by returning functions. For example, in plus n m, plus n is first evaluated, and returns a function which takes an int and adds it to n. Then, this function is called with m as as an argument. Thus, function calls are left associative.

Here, plus maps n to plus n

plus :: Int -> (Int -> Int) (Int → (function which takes an int and gives an int))

plus n maps m to n+m

plus n:: Int -> Int

Thus, the -> operator in a function’s type declaration is right associative. Haskell provides implicit bracketing for both type declarations and function calls. Thus,

f :: Int -> Int -> Int -> Bool means f :: Int -> (Int -> (Int -> Bool))

and

f 1 2 3 means ((f 1) 2) 3.

Sectioning

+ is a binary operator/function. However, it can be combined with other expressions to create simple functions. For example, (+5) is a function which takes one argument and adds 5 to it ((+5) 13 = 18)