Taylor’s theorem

Let be twice differentiable. Fix . Consider the simplest approximation of that can be made: a constant function.

Here, is a constant polynomial approximation, and is the error. Note that . Now, we can try to refine our approximation by siphoning information from the error function. Consider the limit

Let

Clearly, . Plugging in the value of in terms of in the zero degree approximation gives the first degree approximation at .

How would you obtain a second degree approximation? Once more, consider the limit

and let

Again, . Plugging in the value of in terms of in the first degree approximation yields:

where .

is called the th Taylor polynomial at .

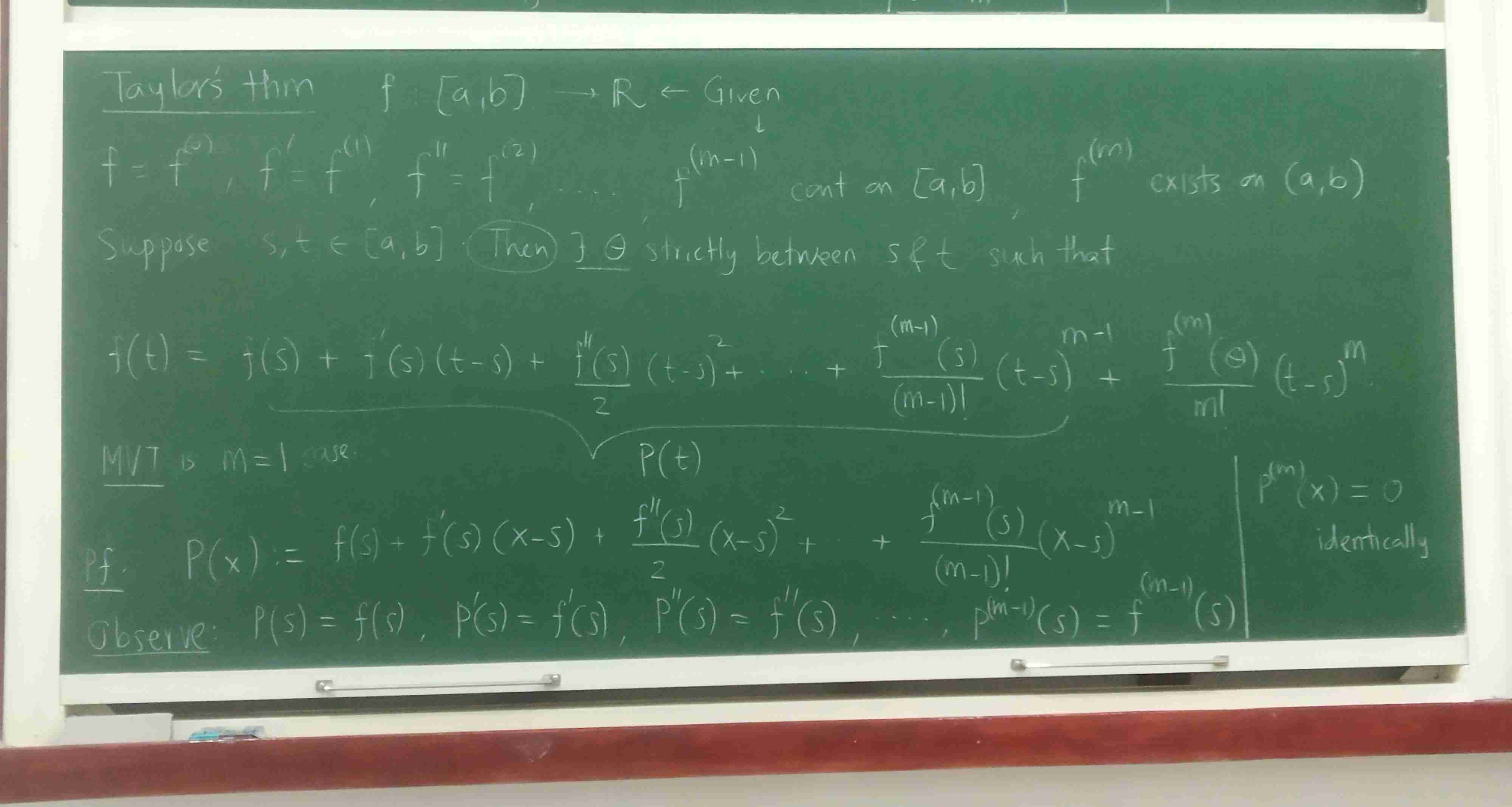

Theorem 147.1(Pugh (2015) 3.12).

Assume that is th order differentiable at . Then

- approximates to order at in the sense that the Taylor remainder is th order flat at ; that is, as .

- is the only polynomial of degree with this approximation property.

- If, in addition, is th order differentiable on then for some we have

Proof.

The first derivatives of exist and equal at . If then repeated applications of the Mean Value Theorem give

where . Thus,

If the same is true with .

If is a polynomial of degree , , then is not th order flat at , so cannot be th order flat either.

Fix and define

for . Note that since is a polynomial of degree , for all , and

Note that , and . By the Mean value theorem, there exists such that . Since and , there exists such that . Continuing, we get a sequence such that . The st equation, , implies that

Thus, works. If , the argument is symmetric.□

Remark 147.2.

is the Lagrange form of the remainder. If for all , then

an estimate that is valid uniformly with respect to and in .

Theorem 147.3(Rudin 5.15).

Suppose , and are continuous on , and exists on . Let .

Then, there exists strictly between and such thatProof.

We have shown that can be expressed as

Let be the number defined by

Define

where . Note that , and . Also note that are zero.

On differentiating both sides times with respect to we get

Now, since and , there must exist between and such that , thanks to the mean value theorem. Again, since and , there must exist between and such that . After steps, we obtain such that . Therefore, .□

If we know that bounds on , we can bound the error!

MVT analogue for vector valued functions

The mean value theorem and L’Hospital’s rule are not true for complex or vector valued functions. For an example of the former, consider the map

. Note that for all . Now,

However, an analogue of the MVT does exist:

Theorem 147.4(Rudin 5.19).

Suppose is a continuous mapping of into and is differentiable in . Then there exists such that

Proof.

Let. Define

Now, is a continuous real function. Thus, the mean value theorem tells us

for some . Also,

Thus,

□